6,500-Year-Old Earthworks in Austria Are Thousands of Years Older than Stonehenge

Around 10,000 years ago, a paradigm shift in human history began to unfold. Prior to this transitional period, which archaeologists refer to as the Neolithic Revolution—the final phase of the Stone Age—small societies were organized around hunting and gathering for sustenance. During the Neolithic period, the gradual adoption of agricultural practices forever changed the way we live.

Over the next few thousand years, humans began domesticating plants and practicing animal husbandry in different parts of the world. And with less time needed for farming than for nomadically searching for food, ancient people could enjoy other activities that led to economic, political, religious, and artistic developments.

The Neolithic period saw the very first civilizations. It’s also when iconically old structures like Ireland’s Newgrange passage tomb and England’s Stonehenge complex were built, the latter of which was begun around 3100 B.C.E. and finished around 600 years later. For context, when Stonehenge was in its final phase, construction of the Pyramids of Giza was likely in progress. Recently, a series of circular earthworks dating to the 5th millennium B.C.E. (5000 to 4001 B.C.E.) in Burgenland, Austria, may predate much of Stonehenge by a remarkable 2,000 years.

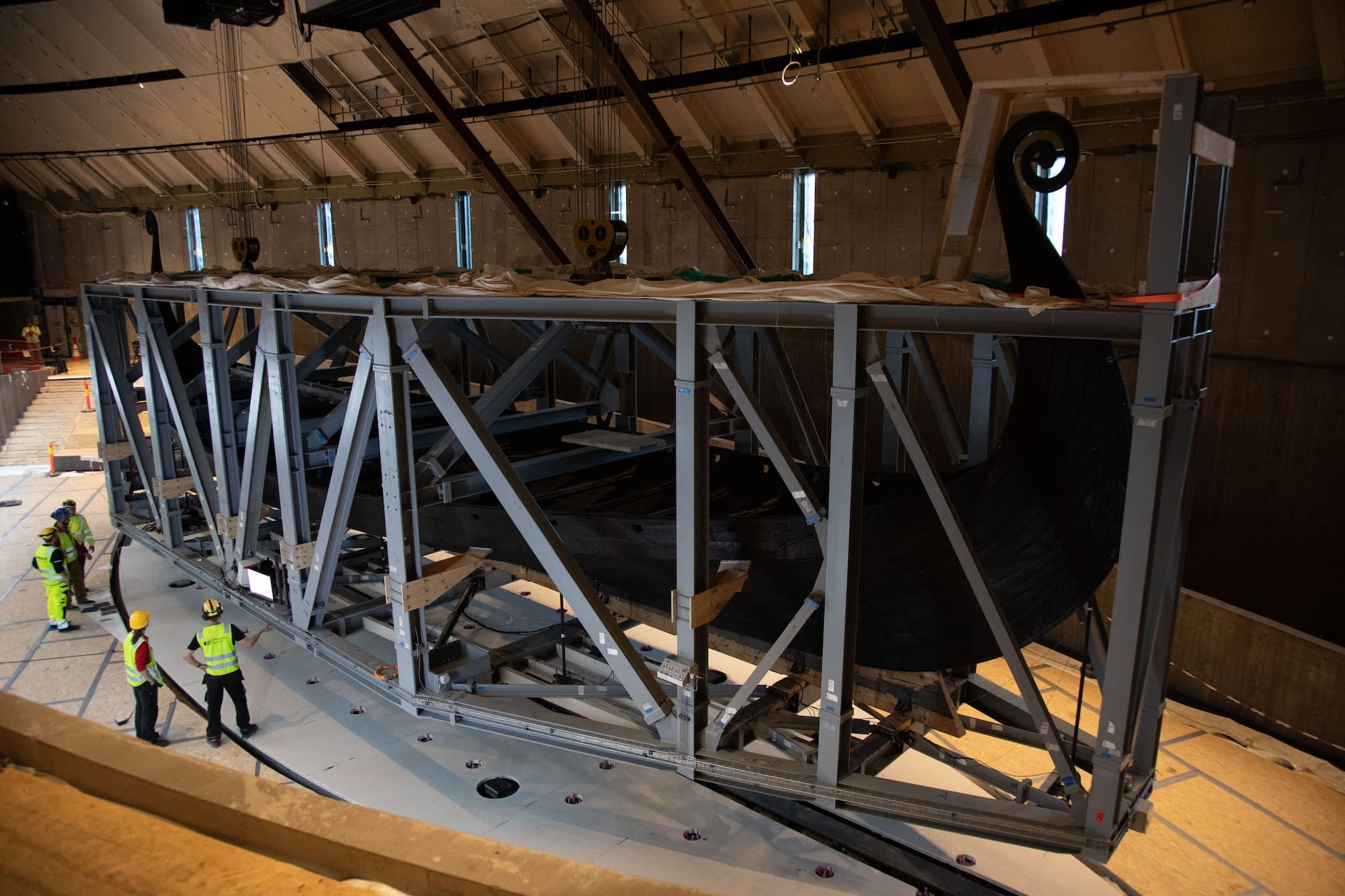

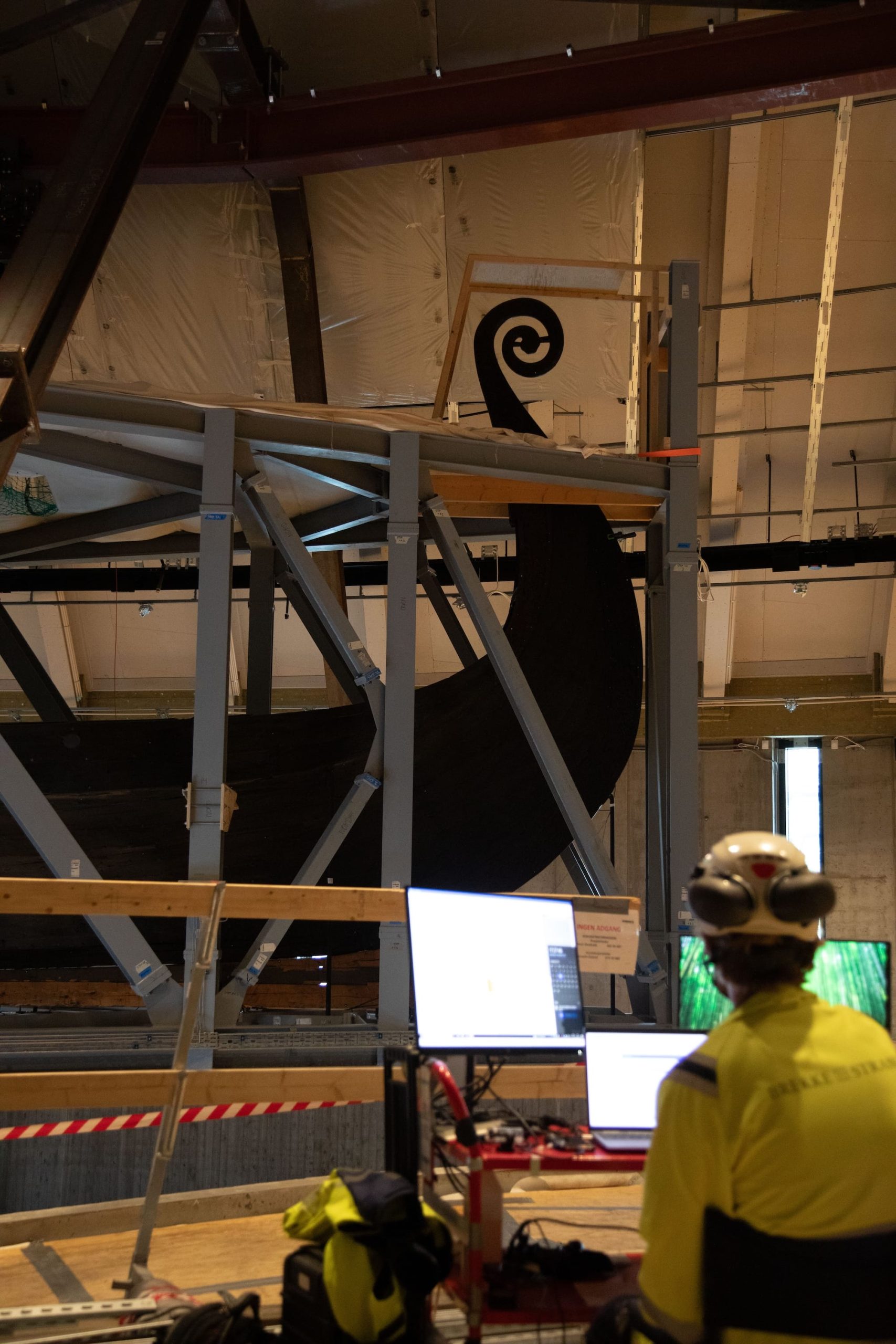

At the newly excavated site, three monumental structures sit in close proximity to one another near the town of Rechnitz. The earthworks were initially discovered via aerial and geomagnetic surveys between 2011 and 2017. A total of four were found, three of which are ring-shaped structures that were previously invisible to the naked eye.

Known as circular ditch systems, the structures were built in the Middle Neolithic period—sometime between 4850 and 4500 B.C.E.—making them at least 6,500 years old.

“The Rechnitz site can be considered a supra-regional center of the Middle Neolithic period,” says Nikolaus Franz, the director of Burgenland Archaeology, in a statement. In the ditches measuring as much as 340 feet across, archaeologists have documented pits containing ceramic finds and post holes that indicate where timber beams in the ground once supported shelters.

Circular ditch monuments of this type, known as Kreisgrabenanlagen in German, are consistently found throughout Central Europe. While their intended function remains unknown, researchers generally believe they held an ancient religious, or cultic, purpose. Similar to Stonehenge, their orientation includes openings that align with the solstices and seem to correspond to an astronomical calendar.

“The excavations open a veritable window into the Stone Age,” Franz says. “We are learning a great deal about the Neolithic settler clans who found this a favorable location to establish the cultural techniques of agriculture and livestock farming in what is now Burgenland…After centuries of hunting and gathering, the gradual settlement of humans was truly revolutionary.”

You might also enjoy exploring the phenomenal complex of more than 10,000 earthworks made by prehistoric Indigenous societies in the Amazon basin.

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $7 per month. The article 6,500-Year-Old Earthworks in Austria Are Thousands of Years Older than Stonehenge appeared first on Colossal.