In ‘Resistance in Memory,’ Sudanese Photographers Bring Critical Visibility to a ‘Forgotten War’

In 2019, a revolution fueled by deep-seated discontent precipitated a coup to remove then-president of Sudan, Omar al-Bashir. Then in 2021, the military led another coup to take control of the government. In April 2023, all-out civil war erupted between rival military groups who sought to control the government: the country’s armed forces and a paramilitary group called Rapid Support Forces (RSF). All results of decades of tensions, the evolving and disastrous struggle continues today.

The conflict has also led to a terrific humanitarian crisis. Despite mounting casualties, millions living in famine regions, and nearly a third of the country’s population displaced from their homes, international media focus has predominantly been elsewhere. In his article for TIME, showcasing the photographs of Moises Saman, Charlie Campbell calls the crisis a “forgotten war.”

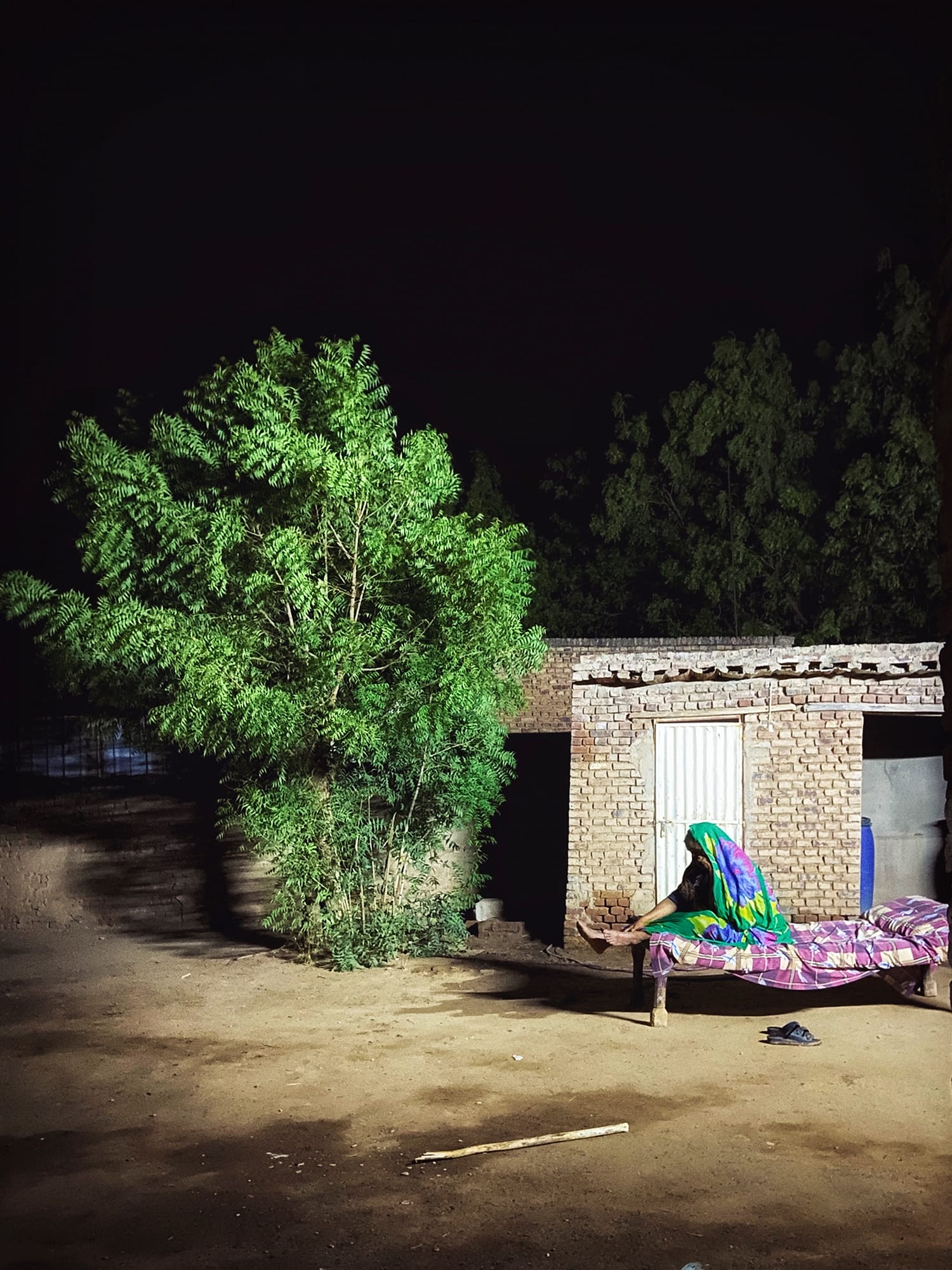

Photographers are our eyes on the ground in Sudan, providing glimpses of the realities of war, displacement, hunger—and hope—in this war-torn nation. Information is tightly controlled and the press heavily censored, which translates to very little insight into events. But images give the crisis much-needed visibility. With this in mind, The Africa Center brings together the work of 12 emerging, independent Sudanese photographers in the group exhibition Resistance in Memory: Visions of Sudan.

Reflections of compassion, love, joy, and humanity ring through the show’s 42 poignant photos, which range from black-and-white landscapes to documentary imagery to portraits. Six of the 12 artists included in the show still reside in the country, sharing personal experiences and observations throughout the last few years.

A statement says, “Resistance in Memory: Visions of Sudan examines the memory of an ever-changing Sudan and the strength and resilience of its people who refuse to be forgotten or defined by those beyond its borders.”

The exhibition continues through March 22 in New York City. Find more on The Africa Center’s website.

Do stories and artists like this matter to you? Become a Colossal Member today and support independent arts publishing for as little as $7 per month. The article In ‘Resistance in Memory,’ Sudanese Photographers Bring Critical Visibility to a ‘Forgotten War’ appeared first on Colossal.